“Scientists can come up with ideas but it’s only when they’re put in practice by crews that they make a positive difference”

Various regulatory and voluntary actions to protect the North Atlantic right whale appear to be having a positive effect. “We’re more than halfway through the 2022 right whale season in Canada and have no known right whale deaths, which is building on two previous years of no known right whale deaths in Canadian waters,” relates Michel Charron, Acting Director of Whale Protection Policy at Transport Canada.

Measures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and linked Canadian waters to reduce vessel collision risks cover more than 72,000 square kilometres – an area larger than New Brunswick. “Compliance with the mandatory elements that cover more than 65,100 km2 is 99 per cent,” Charron adds.

Canada leads the efforts to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whale, according to Moira Brown, Senior Scientist at The Canadian Whale Institute / Campobello Whale Rescue Team. “Transport Canada’s regulatory actions that have vessels avoid certain areas seasonally and lower their speed to 10 knots in specific zones when a whale has been detected are unparalleled,” she says. “It’s also doing a terrific job at enforcement with an investigation launched if a vessel is seen going just 10.1 knots when the speed reduction is in force.”

Brown praises the shipping industry for its 99-per-cent compliance in the regulated zones. “The scientific community can come up with good ideas, but it’s only when they’re put in practice by crews that they can make a positive difference,” she says. “We know the measures add a burden, but Canada and its domestic and international maritime shipping customers should be proud of the hard work being done to better co-exist with this species.”

She and her colleagues from the University of New Brunswick, the Canadian Whale Institute, and the New England Aquarium, set out on a chartered boat from Shippagan, New Brunswick, in early July to newly survey right whales and their habitat in the Shediac and Western Bradelle Valleys.

Moira Brown in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Photo by Delphine Durette-Morin.

Delphine Durette-Morin (left) and Moira Brown (right).

“This year, the whale distribution is a bit farther east in the Gulf of St. Lawrence,” Brown notes. “We want to try find out why. Is that where there’s more food now?”

The last major population shift occurred around 2010. Detections of the North Atlantic right whale decreased starting that year in the Bay of Fundy, but only began significantly increasing in the Gulf of St. Lawrence between 2015 and 2017, according to Charron. Several deaths occurred in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 2017 as a result of fishing gear entanglements and vessel collisions, leading to new precautions being put in place based on the observational research. In 2019, scientists in Canada saw nine deaths, attributing four to collisions and five to unknown causes. That year also saw one entangled whale with serious injuries. Since Canadian protective measures were further updated in 2019, there have been three entangled whales but no known deaths.

On another positive note, researchers identified 15 new right whale calves in 2022 and 19 live calves in 2021. Only 22 births were observed during the previous four calving seasons combined, which is less than one-third the previous average annual birth rate for right whales.

Canadian right whale protection tools

Brown appreciates the multiple resources being provided to mariners, such as the interactive Whale Insight and WhaleMap that indicate online where the whales have been detected visually or acoustically. “In terms of research, surveillance, and putting into place feasible protective measures, I don’t think anyone is working harder than Canada right now to figure out how to help this species,” Brown adds.

Restrictions and slowdowns were introduced in August 2017 and refined in the following years as researchers learnt more about where the whales gathered, and mortalities were occurring. “Adaptability is key as we’re dealing with a changing environment in terms of where the right whales aggregate so we’re using interim orders to have that high level of flexibility,” Charron says. “We also realize that some level of predictability is important to maritime transportation and the measures in place in the Gulf of St. Lawrence with respect to vessel traffic management for the right whale’s protection are essentially unchanged this year from last.”

Transport Canada is consulting with industry, environmental and other stakeholders to reassess the protections in place along an approximately 130-kilometre stretch of the Canadian side of the Cabot Strait where voluntary slowdown guidelines were issued three years ago.

“Although detection rates are quite low, scientists inform us that the vast majority of right whales are moving in and out of the Gulf of St. Lawrence through the Cabot Strait with primary migrations taking place with the spring arrivals and fall departures of the whales – so some form of protection is needed,” Charron says. “We took a voluntary approach on a trial basis to give us time to learn more about the presence of the whales that are difficult to detect there, as well as the challenges of navigating in that channel at reduced speeds.”

Part of the analysis will be to try to determine the factors that lead to either participation or non-participation in the recommended voluntary slowdowns when a whale is detected. “Various factors are in play, including the need to navigate the significant tidal changes,” Charron points out.

The number of ships voluntarily slowing down this year is about one per cent higher than in 2021. Some weeks are lower than a year ago, which is at least partly due to weather conditions, according to Paul Topping, Director, Regulatory and Environmental Affairs at the Chamber of Marine Commerce.

“Our ship operator members are definitely complying as long as safety isn’t an issue,” Topping adds. “However, there have been more last-minute foreign chartered vessels on spot trade – especially with recent supply-chain issues – and some of them may not have been aware of this voluntary measure in time to factor it into their scheduling, while some others may also have been caught in foul weather.”

The Chamber favours maintaining the voluntary measures with vessels continuing to report their voluntary slowdowns.

“It’s a long way to be going 10 knots all the time, and we don’t think there’s the resources at present to make it a dynamic zone whereby the slowdowns would take place only when a whale is detected in the area,” Topping explains.

“Transport Canada is already stretched in surveying the restricted and mandatory slowdown zones and those measures are working well,” Topping adds.

He also notes the challenges of sustaining the existing surveillance because of the cost of running Dash-8 planes regularly. “Burning that fuel isn’t good for the environment,” he notes.

Flexibility in the existing five so-called dynamic zones within the Gulf of St. Lawrence calls for slowdowns only when a whale is detected visually or acoustically, or the zone hasn’t been cleared by either aerial or hydro-acoustic surveillance due to weather conditions.

Various detection methods will likely be continued because of the strengths and drawbacks of each.

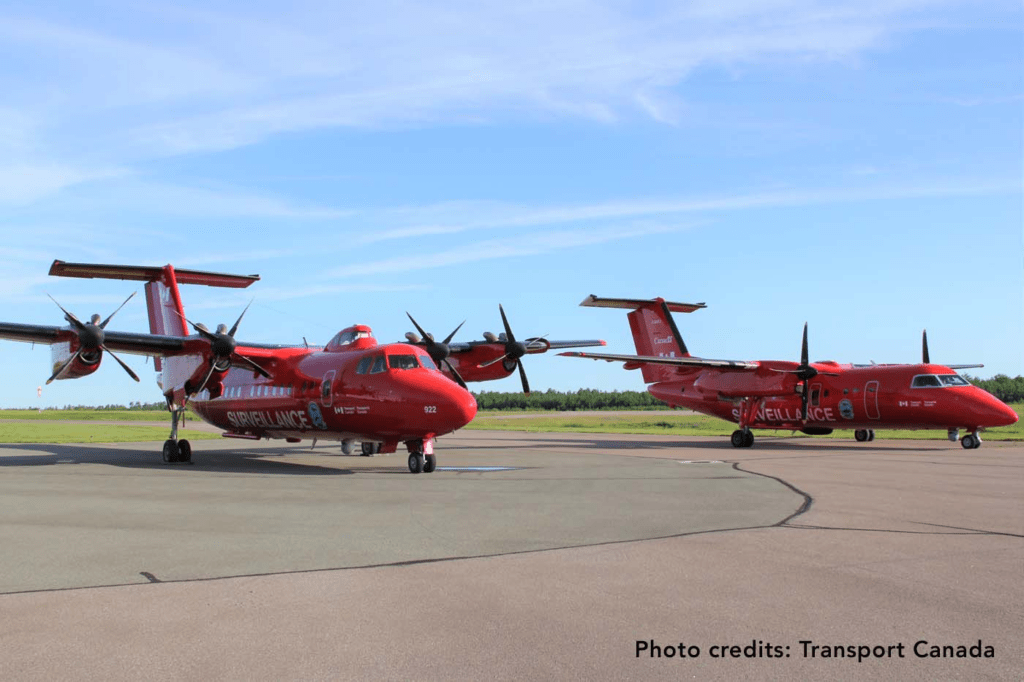

The National Aerial Surveillance Program’s aircraft are Transport Canada’s primary tool to monitor for North Atlantic right whales in the shipping lanes north and south of Anticosti Island and the restricted area. Photo provided by Transport Canada.

Transport Canada uses Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (drone) to complement its surveillance regime to protect North Atlantic right whales. Photo provided by Transport Canada.

“The multi-departmental investment by the Government of Canada in whale monitoring in Eastern Canada is unprecedented,” Charron notes. “And the Government of Canada continues to investigate and invest in new technologies.”

In addition to Transport Canada’s airplane and aerial drone surveillance, as well as autonomous underwater gliders, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has secured hydrophones onto stationary buoys. “The Canadian Space Agency is halfway through a research program with the DFO and Transport Canada that should result in some interesting possibilities in terms of space-based detection,” Charron adds. “We’re also testing infrared technology for the first time this year in terms of right whale detection with cameras set up on Newfoundland’s South Shore as well as on each side of St. Paul Island and on Nova Scotia’s North Shore.”

Canadian ship operators enhance right whale research

Meanwhile, shipping companies, such as Algoma Central Corporation, Canada Steamship Lines, and Groupe Desgagnés, are enhancing the knowledge base about whales and their whereabouts. The shipping lines have embraced whale identification and reporting by crews that initially was based on the printed guide issued by the Marine Mammal Observation Network (MMON), the Shipping Federation of Canada, and Dalhousie University.

Further training on identification and reporting followed with MMON and Green Marine leading onboard sessions. This past spring, the MMON and WWF-Canada with other stakeholders (including Transport Canada, the DFO, the Shipping Federation, and the St. Lawrence Global Observatory, as well CSL, Desgagnés and other lines), developed a site that makes online training readily available for crewmembers and others.

Navigating Whale Habitat has distinct portals for ship owners, commercial fishers as well as recreational boaters to safely navigate whale habitat, identify species, and relate observational data. The crews of more than dozen shipping companies now voluntarily follow the strict protocol to convey their observational data.

“The online training makes it a lot more convenient,” says Caroline Denis, CSL Group’s Senior Project Manager. “Otherwise, it can be difficult to get everyone into a classroom with all the different work schedules.”

“Crews are happy to participate,” adds Daniel Côté, Senior Environmental Advisor at Transport Desgagnés. “Our onboard personnel have always been excited about this initiative knowing they could make a significant contribution to the knowledge about the location and behaviour of these neighbours at sea.”

Photo taken by whale rescuer, Robert Fitzsimmons.

Mira Hube, Algoma Central’s Director, Environment, echoes the enthusiasm related by crews. ‘We have received positive feedback from those who have completed the training and provide observation data on a monthly basis to MMON,” she confirms. “The program is going very well and we’re proud to be participants.”

The need to always keep a keen eye is understood. “The crews will report in real time to the Canadian Coast Guard or Fisheries and Oceans Canada if they encounter a whale in distress that may need immediate assistance,” Hube adds.

With the North Atlantic right whales still numbering as few as 350 individuals, efforts must continue. “What’s great is we have a highly engaged industry at the same table as the academic scientists, environmental organizations and multiple federal government agencies where the discussions are frank and the results are excellent compliance on an adaptable and enforceable approach that is the envy of other jurisdictions,” Charron emphasizes. “Despite varying priorities, none of us wants to see the right whale’s decline so we’re all working really hard together in a positive direction.”

Finback whales photographed by Lise Portelance, first mate on the M/V Nukumi.

Beluga whales photographed by Lise Portelance, first mate on the M/V Nukumi.