“Ship owners are committed to adapting their operations to reduce noise impacts through feasible solutions based on science.”

A growing body of research is dedicated to examining the impacts of human-generated underwater noise on at-risk whales, dolphins, porpoises and other marine life. The activities under study include seismic oil and gas exploration and oil rigs, active military sonar exercises, pile driving for offshore wind-power installations, and maritime transportation.

The dual goal is to understand the precise effects of the noise on the abilities of marine mammals to communicate with each other, find mates, locate food, and navigate safely, as well as identify ways to reduce the impacts and the noise in the first place.

Several organizations and communities in Canada are working towards making significant progress in this area of study. Canada’s maritime industry is also playing a pivotal role in addressing the underwater noise from ships that can affect the well-being of marine life.

The Marine Acoustic Research Station (MARS) project – the first such initiative worldwide – is a prime example. The research is determining the acoustic signatures of Canadian-flagged vessels plying the St. Lawrence to identify and prioritize the causes of noise and find practical ways to make vessels quieter.

“We couldn’t do this research without the collaboration of the ship owners who allow us to not only measure the noise radiating from their ships under water, but to board their vessels to determine the origins,” relates Sylvain Lafrance, Executive Director of Innovation Maritime (IMAR). “Ship owners are committed to adapting their operations to reduce noise impacts through feasible solutions based on science.”

Instrumentation and vibro-acoustic data are collected from a partnering ship owner’s vessel. Photo credit: Kamal Kesour, IMAR.

Model collaboration

Funded by Transport Canada and the Quebec Ministry of Economy and Innovation, the three-year project is now in its second year and co-led by IMAR and the Institut des sciences de la mer de Rimouski at the Université du Québec à Rimouski (ISMER-UQAR).

Algoma Central Corporation, the CSL Group, and Groupe Desgagnés are among the ship owners taking part as well as providing financial and logistical support. Other key partners include OpDaq Systèmes, which is sharing its engineering expertise, while Multi-Électrique (MTE) is providing sound-recording technology. “This project is a superb model of collaboration in applied research,” Lafrance notes.

MARS has world-class instrumentation in the St. Lawrence Estuary, off Rimouski’s shores. The first component is using sophisticated hydrophone equipment to measure both ambient and radiated noise from the ships. “We’ve established a protocol for vessel operators, so they go just slightly out of their way to pass through the station that records the sounds of that particular vessel,” Lafrance explains.

The onboard component was added this past summer. Microphones along with tachometers and accelerometers were used to identify machinery’s noise and noise-causing vibrations. “We’ve established a set way of collecting this data to establish the link between the noise generated aboard and then radiating under water,” Lafrance explains. “This will help us to identify the major sources of noise and determine how noise levels change under different environmental and operating scenarios.”

The goal is to establish noise-quieting protocols that ship owners could readily put in place. “We’re looking at all the individual components – each pump, every engine – to determine their effect on the vessel’s acoustic signature,” Lafrance says.

The MARS site was selected for its adequate depth, modest current and other characteristics that lend themselves to proper data being obtained from hydrophone readings. Each vessel passes through MARS at a consistent speed between eight and 14 knots. “The different speed rates help to determine how that influences noise generation,” Lafrance adds. AIS tracking ensures other ships aren’t contributing noise to a vessel’s acoustic signature.

When the project concludes next year, each ship owner will be given a detailed report with the acoustic signature of each of its participating vessels. “We’re also preparing a report for Transport Canada that will provide information on the noise signature of the different types of vessels at different speeds without specifically identifying them.”

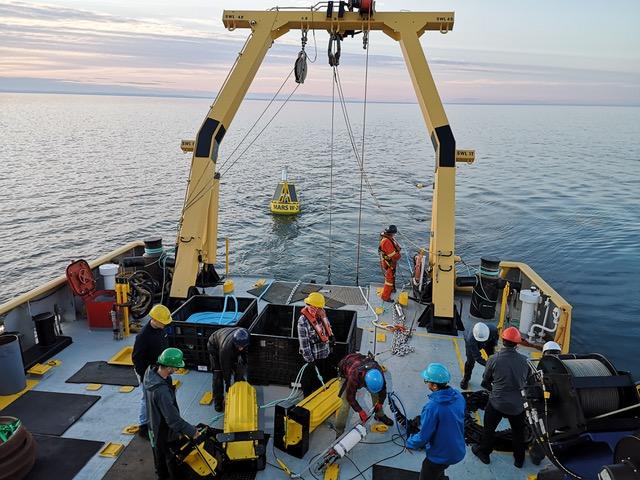

The MARS team launches the acoustic antennae from aboard the RV Coriolis II research vessel. Photo credit: Charles Massicotte, MTE.

Voluntary improvements

Green Marine, a voluntary environmental certification program for the maritime industry, undertook a global survey of existing research for Transport Canada in 2015. Green Marine’s membership subsequently identified underwater noise as an issue requiring action and committed to reducing its related impacts. In 2017, the Underwater Noise performance indicator was added to the program for ship owners and port authorities.

With this performance indicator, Green Marine calls upon ports to inform and ultimately incentivize ship owners to take actions to measure and subsequently mitigate noise in the program’s Level 1’s monitoring of regulations to Level 5’s excellence and leadership self-evaluation scale. It also requires ports to be aware of ecologically sensitive areas so traffic can be diverted or slowed.

At Level 2, seawater ports must obtain the services of a marine mammal observer to check for the presence of at-risk species during water-based construction so that work is halted until the animal(s) leave the area. The Saguenay and Sept-Îles port authorities have each reached Level 3 with a mitigation and management plan of actions for addressing underwater noise issues.

“I expect more ports to reach Level 4, which involves setting noise reduction targets, once the MARS protocols are established,” Green Marine Program Manager Véronique Trudeau adds. “And, of course, the project is so important for ship owners to know what’s causing the most noise and how to reduce it.”

Under Green Marine’s Level 2 requirements, ship owners must already carry out best management practices, such as hull cleaning and propeller blade maintenance to reduce noise-causing friction and cavitation respectively. “They must also be aware of sensitive areas and participate in voluntary traffic measures to protect at-risk marine mammals,” Trudeau says.

Level 3 involves collecting and providing data to scientific organizations and to develop a marine mammal management plan. The MARS research is expected to help more ship owners to achieve Level 4 which involves employing quieting technology during retrofits or new vessel construction. Level 5 necessitates an in-depth noise analysis of at least one vessel.

Green Marine is actively involved on behalf of its membership in obtaining more knowledge and information. The organization serves on the North Atlantic Right Whale Stakeholders Committee led by the Canadian Wildlife Federation. It is also involved with the advisory and technical working groups lead by Transport Canada, as well as the Working Group on Marine Traffic and Protection of Marine Mammals (G2T3M) in Quebec.

Marie-Laurence Bazinet, a member of the IMAR team, is involved in the acoustic diagnostic operation aboard a ship. Photo credit: Kamal Kesour, IMAR.

Balancing act

Existing research indicates that underwater noise disrupts the normal behaviours of whales, making it harder for them to communicate or to echolocate each other or their food. Human-caused noise spooks them in the way predators would and increases their stress levels. Scientists working in the Bay of Fundy coincidentally discovered that a stress-related hormone in North Atlantic right whales lowered during the near-standstill in ship traffic in the days after Sept. 11, 2001.

The issue is complicated. “We must be careful that we don’t exacerbate climate change in the process of installing quieter propeller designs, for example, that require more fuel to operate,” notes Paul Topping, the Director of Regulatory and Environmental Affairs at the Chamber of Marine Commerce. “New research suggests that underwater noise is affecting plankton – a major food source for whales – but the need to protect marine life must always be done in alignment with the urgency to reduce greenhouse gases.”

Efforts are under way already. A cavitation monitoring system has been developed and installed aboard CSL’s Ferbec bulk carrier to understand the extent of underwater noise emitted by the vessel’s propulsion system. “Given that cavitation accounts for 80 to 85 per cent of the underwater noise, this real-time information can help a bridge to determine whether it can reduce cavitation, particularly in ecologically sensitive areas,” relates Caroline Denis, CSL’s Senior Project Manager.

CSL is also reducing noise by installing main engines on resilient mounting, and propeller boss fin caps on existing vessels. Last January, CSL welcomed the first diesel-electric lake vessel into its fleet. “We believe the quieter machinery and twin-fin-diesel-electric propulsion make the Nukumi a much quieter laker, but this remains to be confirmed with the vessel’s first passage in the MARS station,” Denis says.

“The MARS project has given us the wonderful opportunity to evaluate our ships at different speeds, engine rpm and pitch combinations to determine the quietest combinations,” Denis adds. “We’ll have actual measurements of engine room components to evaluate if their vibration is causing significant noise.”

Algoma’s efforts to reduce underwater noise in the design of its newest Equinox Class include incorporating a pram gondola stern. The design is similar to the upward curve at the back a traditional pram/baby carriage for a smoother and quieter flow of water along the back of the vessel. The gondola shape where the propeller is installed lowers the water being churned which spreads out the propeller’s wake more evenly. A costa bulb installed on the rudder behind the propeller additionally smooths out the ship’s movement by reducing turbulence that may cause drag and/or underwater noise.